Published in May 2020 and written by the boundary-breaking and eccentric mycologist Merlin Sheldrake, PhD, Entangled Life is a rich and enchanting book about the wonders of fungi. It is an eye-opening book, frequently throwing seemingly simple facts into new light. The book doesn’t stand alone, it has hundreds of notes that signpost to further reading, multiple accompanying videos and even music inspired by or tied into the book that can easily be found online. Although every page is filled with extraordinary information about fungi, the book has a wider aim; to challenge the reader’s perception of science. To achieve this, the book must entice a reader and encourage them to start the book, hold their attention throughout and then enable further exploration and conversation of the subject matter. This analysis will explore how the book affects the reader and assess its success in engaging the audience and shaking perceptions of science.

Sheldrake uses ground-breaking research on fungi as a tool to change the reader’s outlook on the world. He describes how his studies have shaken his own views: “the more I’ve studied fungi, the more my expectations have loosened, and the more familiar concepts have started to appear unfamiliar” (Sheldrake, 2020. pg 16). In contrast to the bulk of factual science communication which takes care to distinguish between scientific work and non-scientific intellectual work (Gieryn, 1983), Entangled Life blurs these boundaries and argues that imagination is needed to understand science. This challenges the reader: normally, science is thought of as being – and scientists are trained to be – objective. However, in this book Sheldrake is anything but objective; he anthropomorphises mushrooms and mycelium and even encourages the reader to consider how it would feel to be a fungus. This encourages a new outlook on what science really is.

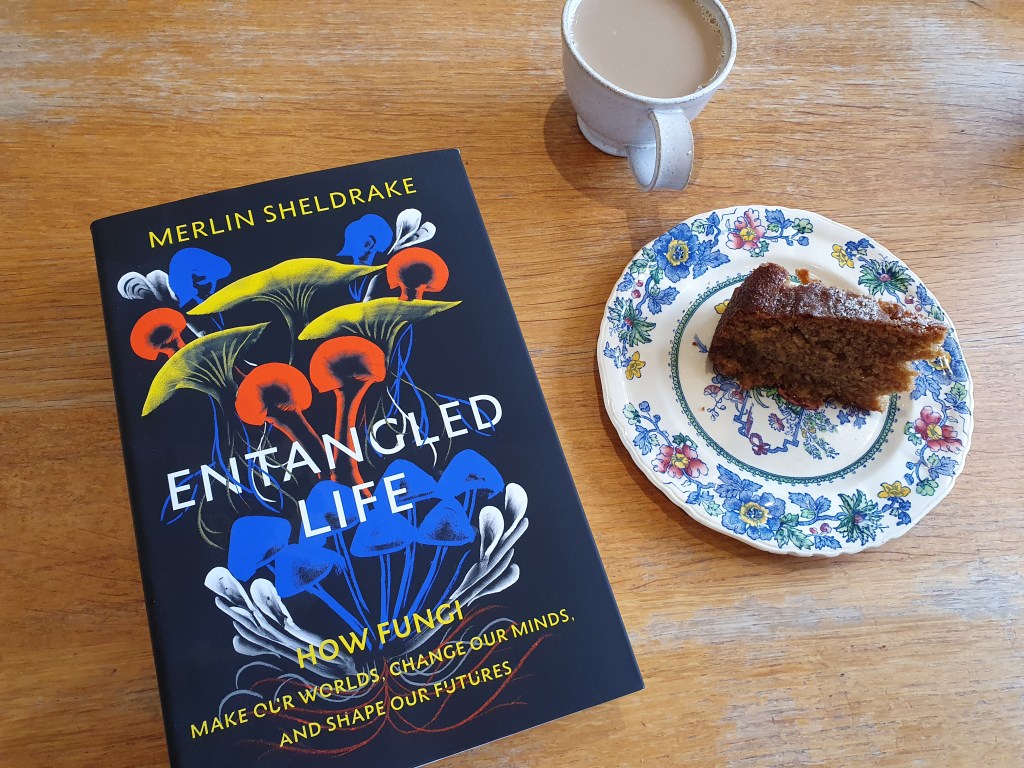

Before challenging any preconceptions, Entangled Life must be read. Those who would choose to read Entangled Life are probably already somewhat engaged with the natural world and popular science fiction. Therefore, it cannot be said that the intended audience is the entirety of the general public, rather it is a limited portion of the public which chooses to engage with this type of science, although they are not all experts. As Bell and Turney (2014) explain, popular science books “assume interest”, though not “expertise” from the reader. The book, currently published in hardback, features a striking illustration of mushrooms against a black background, the worlds ‘Entangled Life’ literally entangled amongst hyphal strands. It is modern, attractive and eye-catching, increasing its chance of being picked up by a prospective reader. Once started, the book uses a range of different tools to keep the reader engaged. From early on, the reader is shown how fungi relate to them on a personal level. Importantly, the book’s tagline reads ‘How fungi make our worlds, change our minds and shape our futures’. This immediately acts to contextualise the book in relation to the reader who might ask oneself, ‘how do fungi affect me?’ In the introduction, the reader learns how vital fungi are for a huge proportion of life on Earth. For example, one learns how fungi allowed the terrestrialisation of plants, how certain fungi are able to control minds, the role of fungal spores in seeding rain and how fungi even are important in the production of vaccines. The reader learns, most likely with surprise, how integral fungi are to their very existence, keeping them engaged with the book.

An important way in which the book engages the reader is through story-telling. Entangled Life is an ‘expository’ book, covering in great detail many varied aspects of mycology, the study of fungi (Mellor, 2003. Pg 4). However, it is also often ‘narratival’ (Mellor, 2003. Pg 4); Sheldrake takes the reader on a journey of his experiences, whether that’s truffle hunting in Italy or on an LSD trip in an experimental lab. These narrative aspects help to draw in the reader and provide context before the chapter embarks on the more expository (i.e. detailed) aspects of the science (Mellor, 2003. Pg 4). Kahneman (2011) states that there are two main systems of mental processing. System 1 is involved in creating stories and has a strong basis in imagination whereas System 2 is involved in complex problem-solving. ElShafie (2018) argues that writers of science should not rely on their reader’s System 2 cognition but that they should regularly engage the reader’s System 1 cognition (ElShafie, 2018. Pg 3). By using narrative, story-telling portions within each chapter, usually at the start and then interwoven throughout, Sheldrake exploits the reader’s imaginative System 2 cognition alongside System 1 cognition, effectively keeping the reader engaged. This allows the presence of highly detailed scientific paragraphs and yet limits any potential reader disengagement.

Imagery plays an important role in Entangled Life. Throughout the book, Sheldrake breaks up the text with simple illustrations. On page 8, a figure legend of one reads, “Shaggy ink cap mushrooms, Coprinus comatus, drawn with ink made from shaggy ink cap mushrooms”. The image relates to what is being discussed in the main body of the text and is more evidence of Sheldrake challenging the reader’s assumptions: mushroom ink is most likely a new concept, and therefore the reader looks at the illustrations in a new light. It is widely accepted that visualisations of science are important in engaging and inspiring the reader, but for best effect different types of visualisations are needed (Iwasa, 2016). In the centre of Entangled Life there are eight sheaves of glossy paper exhibiting coloured illustrations, diagrams and photos. These varied images provide context to the reader, exhibiting the science and ideas that are difficult to picture in the mind’s eye, while also introducing new ways to perceive the information. Furthermore, they add credibility to the book as many of the figures originate from scientific papers.

As with many popular science books, Entangled Life is not simply a text bound by a cover. Mellor (2003, Pg. 9) writes “popular science books form nodal points in an intertextual web stretching across all the mass media”. This is the case for Entangled Life; it has a far-reaching aura of different media and the book is only a starting point from which further exploration is encouraged. After the epilogue, there are 45 pages of notes that relate to almost every paragraph of the book. These notes range from contextualising information, to signposts to further reading, to links to videos. For example, in the chapter ‘Living Labyrinths’, Sheldrake discusses research from the University of California which visualises nuclei moving along hyphae (pg. 64). At the end of this paragraph, a small 22 sits above the full stop. You can find its corresponding note on page 269: a reference and the line “Videos available on YouTube: ‘Nuclear dynamics in a fungal chimera’”, followed by the URL. The video is extraordinary, showing thousands of nuclei streaming through threads of mycelium like “traffic within a city” (MycoFluidics, 2013). If the reader takes the time to find this video, YouTube will most likely suggest similar videos, allowing guided yet self-motivated exploration around the topic. Entangled Life provides the reader with the tools needed to explore that which they find interesting within the text.

The pictures and the media reconfigure the reader from being a passive subject to an actively researching individual. By encouraging the reader to follow links, watch videos and choose their own interests, the book moves away from the rigid deficit model of communication as the reader is not passive in receiving information from an expert in a linear, directional fashion (Trench, 2008, Hilgartner, 1990). The book and its media align better with Lowenstein’s (1995) web of science communication, in which all aspects of a source link to others closely related to it. The reader is allowed to choose their own path. The deficit model is further challenged as Sheldrake does not take the position of an ‘expert’ with all the answers. The idea of the popularisation of science developed by Hilgartner (1990) argues that scientists produce knowledge which is then simplified (or distorted) when conveyed to a public. This model also says that there are two agents involved: the scientists and the populariser. In the case of Entangled Life, there is no doubt that the book expresses the science in a way that is simpler than the published papers (I doubt the book would be so popular if this were not the case) however, the science is not distorted by this simplification. It is presented as clearly as possible, though the book makes of point of demonstrating how complex the science is and that there is still much that the scientists do not know. This book challenges Hilgartner’s view of popularlisation as what we don’t know cannot be simplified. Furthermore, the science that is known is explained carefully with notes, further explanations and clear signposting to references to those who want the complexities. The book introduces us to professional researchers with doctoral degrees who work for esteemed institutions, however it also discusses the importance of amateur mycologists and citizen scientists who are doing ground-breaking work in the field of mycology (Sheldrake, 2020. Chapter: Radical Mycology). This allows the reader to imagine themselves in the role of an amateur mycologist; the reader is empowered to believe that they could get involved in some way. Again, this is another example of Entangled Life blurring the barriers around what it means to be a scientist and an expert while also attempting to veer away from a deficit model of communication.

There are few empirical ways to ‘prove’ that the book successfully achieves its aim in challenging the reader’s preconceptions. Simply as a book, Entangled Life has been successful: on Amazon’s bestselling list it ranks at 311 out of all books, and number one in the categories ‘Forestry and Silviculture’, ‘Mushrooms and Fungi’ and ‘Plant Sciences’. Out of 324 ratings, 85% are five-star and 10% are four-star (Amazon, 2020). Similarly, on the Waterstones website the book has six reviews, all giving Entangled Life five stars (Waterstones, 2020). Reading the reviews themselves are insightful, for example Caroline Thomas writes, “Absolutely fascinating and ground breaking. So eloquently written and the research is thorough and referenced throughout… I read it with increasing excitement about what is possible” (Amazon, 2020). Of course, although the book might have a limited readership it is important to note that having becoming BBC Radio 4’s ‘book of the week’ on November 23rd, many more people will have been exposed to the book and its aura than those who might have chosen to read it (BBC Radio 4, 2020). Looking at the book’s media is also useful. In its epilogue (Pg. 251), Sheldrake states that once the book is published he will grow mushrooms on a copy. The subsequent video of Sheldrake eating these mushrooms has over 31,500 views (Merlin Sheldrake, 2020). The comments on this video address the success of the book’s aims. ‘Causeway’ writes, “I’m about 100 pages in and already it’s having an effect on how I view the world”. Sheldrake doesn’t claim he wants to change everyone’s outlook on the world and therefore evidence of even a limited number of people saying that the way they think has been changed suggests that the book has achieved its aim.

As outlandish as some of the claims within the book seem, they are carefully explained and evidenced and anything the reader wants to learn more about is clearly signposted in the book’s extensive notes. Sheldrake ends the book’s introduction saying, “My hope is that this book loosens some of your certainties, as fungi have loosened some of mine” (page 25). There is no doubt that this book succeeds in doing so for those that read it. Sheldrake’s use of pictures, media, narration and scientific experts convincingly shake up the traditional view of science and reveal new ways of thinking about the world around us.

Bibliography:

Amazon (2020). Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures Hardcover – 3 Sept. 2020. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Entangled-Life-Worlds-Change-Futures/dp/1847925197/ref=sr_1_1?crid=2WEQY209ISEGL&dchild=1&keywords=entangled+life+by+merlin+sheldrake&qid=1605954978&quartzVehicle=45-608&replacementKeywords=entangled+by+merlin+sheldrake&sprefix=entangled+life%2Caps%2C369&sr=8-1 (Accessed: 20 November 2020).

BBC Radio 4 (2020). Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake. [Radio Broadcast]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000pm12 (First Broadcast: 23 November 2020, Accessed: 24 November 2020).

Bell, A. & Turney, J. (2014). ‘Popular science books from public education to science bestsellers’, in Bucchi, M. & Trench, B. (eds.) Routledge handbook of public communication of science and technology, 2nd edition Routledge international handbooks. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 15-26.

ElShafie, S. J. (2018). ‘Making science meaningful for broad audiences through stories’, Integrative and Comparative Biology, 58(6), pp. 1213-1223.

Gieryn, T. F. (1983). ‘Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science – strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists’, American Sociological Review, 48(6), pp. 781-795.

Hilgartner, S. (1990). ‘The dominant view of popularization – conceptual problems, political uses’, Social Studies of Science, 20(3), pp. 519-539.

Iwasa, J. H. (2016). ‘The scientist as illustrator’, Trends in Immunology, 37(4), pp. 247-250.

Kahneman, D. (2015). ‘Thinking, fast and slow’, Fortune, 172(1), pp. 20-20.

Lewenstein, B. V. (1995). ‘From fax to facts – communication in the cold-fusion saga’, Social Studies of Science, 25(3), pp. 403-436.

Mellor, F. (2003). ‘Between fact and fiction: Demarcating science from non-science in popular physics books’, Social Studies of Science, 33(4), pp. 509-538.

Merlin Sheldrake (2020). Merlin Sheldrake eats mushrooms sprouting from his book, Entangled Life [YouTube]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJfDaIVl-tE (Accessed: 22 November 2020).

MycoFluidics (2013). Nuclear dynamics in a fungal chimera [YouTube]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_FSuUQP_BBc (Accessed 21 November 2020).

Sheldrake, S. (2020). Entangled life. London: The Bodley Head.

Trench, B. (2008). ‘Towards an analytical framework of science communication models’, in Cheng, D., et al. (eds.) Communicating science in social contexts: New models, new practices. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 119-135.

Waterstones (2020). Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures (Hardback). Available at: https://www.waterstones.com/book/entangled-life/merlin-sheldrake/9781847925190. (Accessed: 20 November 2020).